ArchivesResources

Pet First Aid: Guest Speaker Olivia Moore

Image SOS: Episode 1

Welcome to the first episode of Image SOS!

The idea with this series, is to give you a range of tools and strategies to fix potentially problematic images. There’s a couple of important things to note, however:

- having these videos is absolutely not a reason to ignore the lighting, composition, and so on in your photos. Editing these kinds of problems often is extremely time-consuming and requires a lot of skill.

- To that end, you might find that if you are an Explorer/beginner, you are making some of these mistakes and really want to fix them, but this video might be beyond your skill level. Unfortunately while these are the kinds of mistakes beginners make, they can really only be fixed once you have some decent Photoshop skills.

- these photos were NOT edited to “final product” standard. I wanted to set a decent base for each of them from where I could do more final/fancy edits, or show you skills that were useful in each image, for example, in one I edited out a harness, but I didn’t edit out the collar in the other photo. The process is the same, I didn’t need to show you twice.

- These photos will likely not be “perfect” at all, simply because of the issues with light, composition and so on. I could spend another couple of hours working on them, but I really don’t think it’s necessary.

Here are the images from this episode:

Before

After

Snoot School: Back-up, chin down, hide

So sorry that I didn’t make my window bigger, I forgot that the recording would then record ALL the people/empty windows. Hopefully you can still see everything ok.

20 Minute Tutorial: Merge Two Photos (Headswap!)

This is a very quick tutorial which shows you an easy way to combine two layers into one using masking.

I don’t go over the exact specifications for masking – we will be covering this in the April Workshop. But I do explain each step, and the keyboard shortcuts are shown on-screen, so even people quite new to photoshop should be able to follow along.

Being able to merge two photos like this is incredibly powerful:

- We can take group photos with a narrow depth of field and merge them together so each dog is in focus, rather than having to use a narrower aperture to try and get them all in focus.

- We can fix issues when one dog’s expression isn’t ideal (as in this situation)

- We can take parts of the background, copy and paste it, and mask it in using the same technique

- We can bring in the lower or upper part of a frame from another photo and mask it in using the same technique.

Being able to mask in two different photos in this way will mean you are easily able to fix and change a ton of accidental mistakes in your images, improve composition, potentially improve expression and more. Just remember: white = show that layer. Black = hide that layer. Some people say: “White reveals black conceals” but this was too much of a rhyme and I couldn’t ever remember which way was which. Make up your own memory trick like: “You can see the light (white) but you can’t see through the dark (black)”? Or I don’t know. Whatever makes sense to you.

The main thing behind the scenes is that both photos need to be more or less the same – you’ll see in this one that Loki had moved slightly and I had completely changed my leg position, but since all we needed was Loki’s head and that was in exactly the same position, it wasn’t a problem.

For things like adding parts to the bottom or top of the image, or merging in backgrounds, the plane of focus needs to be the same (eg., the main photo can’t have focus on the person/dog, and the one you’re masking in have focus on the background). The more similar the two photos are, the easier your life will be!

Also my brain was a bit all over the place so apologies in advance for a couple of “squirrel” moments.

How to: Take & Edit Photos of Black Dogs

Table of Contents

There seems to be this idea in people’s minds that taking photos of black dogs is the holy grail of photography. That they are somehow the most difficult coats to take photos of. In this how-to guide, I’m going to equip you with some tools to go confidently into your next photoshoot with a black dog, and begin to consider that they might actually be easier in some ways than, for example, coloured dogs.

It's All About Light

As with everything in photography, photographing black dogs is all about light. How much, where from, how strong, what temperature and so on. For some reason there seems to be this idea that while a “normal” dog can be photographed on overcast day, somehow the entire light of the entire sky won’t be enough to illuminate a black dog, so people try photographing them in the full sun.

All these dogs are so shiny. And I think the thing that gets me is that all this shine tends to make them look quite grey. People worry about lightening up black dogs cos they’ll turn grey, but then go and take photos of them in these conditions. Anyway.

If you’ve worked your way through ANY of the two non-editing courses (and I hope, if you’re here, that you have) you’ll know that harsh sunlight flatters NOBODY. Especially not black dogs.

In my opinion, black dogs go insanely shiny in full sun. SO SHINY. Some people really like this shine, but I find it kind of ugly. Maybe you have to make up your own mind here but it’s certainly not my favourite thing. Not to mention all the crazy shadows and tiny catchlights which come from taking photos in the full sun.

I would even go so far as to say that late afternoon light, when the temperature is warm, can also be problematic to black dogs when it is direct light, as their coats reflect colour so easily.

So now that I’ve completely terrified you away from taking photos of black dogs in any kinds of lighting conditions, what can you do?

As With Every Dog: Get Enough Light

The main thing, is to get soft, even, flattering light on the face. Like with every dog in every photo we’re taking.

Staying on the edge of the woods, in a clearing, or by a road will make sure plenty of light from the sky falls on the face. Check out the Locations lessons if you’re in the Learning Journey, under Creating > Locations. We want to avoid especially deep shadows, or situations where we need to really under-expose the dog so we don’t risk “clipping the blacks” or even just making the black dog so dark that trying to lighten him results in a lot of noise.

Balancing the Light

As with every dog and every photo we’re aiming to balance the light. This means (in general), highlights not blown out, BUT not underexposing so much that you can’t get detail back in the dog. This will be different for every camera, and varies for ISO. I know a friend’s camera will start to really show a lot of grain and loss of detail if she has to raise the shadows very much at ISO 320. Mine is pretty fine until it’s over ISO 1000. That being said, on photos like the one below, which is ISO 200, Loki is so underexposed that I had to raise the shadows a lot in order to simply SEE him. And this was extremely noisy.

So there is a balance between how much you can/need to lighten the black dog, the ISO, and what your camera can handle.

Focus Issues & Black Dogs

One problem I’ve heard from members of the LC is that their camera struggles to focus on their black dog, when they have to underexpose the image due to backlight or similar.

We talked about this in the March Q&A.

What we have to remember is that our cameras generally look for areas of contrast, to know where to focus. So when we have a black dog in an underexposed situation, especially if their face, eyes, or lighting situation don’t really give them catchlights in their eyes, we just have a black blob in front of the camera. So it looks around and goes 🤷🏻♀️ and focuses somewhere. Because there’s nothing to say: “This is one part of the subject, and this is another part”, it’s just all dark.

OR… it will find the shiny contrast of the dog’s nose, and focus there.

If this is happening, you have a few options:

- Make sure you’re using a single-AF point and positioning it over the eye. We need to not really give the camera a lot of options as to where to focus.

- Find an area with more light on the dog’s face, or even use a reflector to bounce more light onto the dog’s face. We really need to create some contrast for the camera to find, particularly in the eyes. Try also getting the dog to raise their face slightly, to get more light reflecting from the sky.

- Underexpose less. Yes, you may need to blow out the highlights. If the choice is between your dog not being in focus, and the highlights being slightly blown out… I know which is more important to me.

- If your camera is consistently focusing elsewhere even when there’s plenty of light on the dog, make sure you check out the focus lessons to try and diagnose the problem.

Backgrounds

Be very aware of your backgrounds with black dogs. We need to really help them stand out and be separated from their background, but also not be overwhelmed by their background (yes, it’s a balancing act!).

- Putting your black dog against a dark tree stump/trunk/dark bush is going to make him blend in, particularly if there are ANY bright areas in the image (eg., bits of open sky or bright bokeh spots)

- Putting your black dog against a very bright area might contrast him, but also he can get “overwhelmed” by the brightness, especially if it’s busy.

So, where can you put your black dog?

Solid, mid-toned backgrounds work very well. That means they aren’t too bright, and they aren’t too dark. The editing tutorial of Šaj below is a good example of a “mid-toned” background.

Backlight also works pretty well IF it’s well-filtered and not overpowering. This is because the rim light can help the dog have a lot of separation from the background. They are glowing, we can easily see the shape of them, and this glowing light draws our eyes to them as well.

1. Using backlight & rimlight for a dramatic black dog in dark environment photo. 2. Low-contrast, mid-tone background. 3. An example of when Loki is in a “dark area” and would easily become overwhelmed by the light areas of the photo. 4. Low contrast mid-tone. 5. Mid-toned background. 6. Backlight. 7. Putting him in a dark hole (I could edit this, but getting separation would be difficult still, but I could use it for a dramatic deep/dark forest effect IF he didn’t look so cute.). 8. Getting overwhelmed by light in the background. 9. Low contrast, mid-toned background. Light directly behind to contrast his dark. 10. A kind of “tunnel of light” (soft light) behind him, to contrast his dark fur against. Eye is drawn to the light -> dark dog is in the light. 11. Dark dark dark, but fun as a dramatic effect and certain mood. 12. Backlight to help her stand out. 13. Mid-toned background. 14. Mid-toned background (old photo, I would turn down the bokeh a bit more now). 15. Backlight and monotone colours.

Balancing Black & Grey

One of the other main issues people run into, is balancing black and grey. It’s very easy, when lightening up a black dog (especially when raising shadows!) to end up with a washed out grey dog!

And it is a balance. Without light, we can’t see the details of the dog. With too much lightening, we have a grey dog. The main thing to remember here, I think, is that our eyes make sense of things based on light AND dark. We can’t tell what is bigger or smaller, in or out, without areas of light and areas of shadow.

What I’m saying is, don’t be afraid of blacks and shadows. Our dogs are black. Without blacks and shadows, we loose the contrast that TELLS us they’re black. One of the ways I make my black dogs look lighter, is to contour their face with darkness. By adding darkness to the shadow/inward parts of their face, it gives contrast compared to the light parts of their face – essentially, making the light parts look lighter!

It’s like how if you’re editing a photo, and you have the background of Lightroom or Photoshop set to light grey or white. Your photo then probably seems really dark, right? Try setting the background to black. Now your photo looks really light!! Nothing has changed except the shade around the photo and the contrast for our eyes between the light and the dark.

These two images are exactly the same. Notice how the one on the black background looks much lighter and has more detail in the surroundings than the white background image?

So yes, we want to be able to see the details of a black dog. We also want to keep them a nice, rich black. Don’t be afraid of adding some contrast to their fur.

Contrast

One more note on contrast, is that contrast can help our dog stand out, if there is no contrast in the rest of the image. Our eyes are drawn to contrast, and contrast is particularly visible when compared to areas of low contrast. So, by making sure our dogs are a rich black with plenty of contrast, and removing contrast from their surroundings (by raising the blacks, for example), this will also help them to stand out.

Blue Dogs

Another thing to be conscious of is the fact that black dogs reflect colours – particularly blue. Blue dogs is one of the main issues I see with people editing black-coated dogs.

You can sometimes use the space between the dog’s eyes as a place for the “Eye-Dropper tool” in Lightroom, to tell it that the area should be pure black. But, this is assuming the dog IS pure black. Many dogs have a lot of red/brown undertones in their coat, even if it’s VERY subtle. I’m looking at Loki’s fur in the sun right now (and he is about as black as black gets, apart from the edges of his ears) and there is definitely brown in his coat. Therefore, if I used the eyedropper on his black coat, it would probably shift things too much to blue (cancelling out the yellow) or to green (cancelling out the magenta).

A better tool is to turn the saturation up to 100 and then adjust the white balance. Because the black coat is made up of brown (magenta/yellow), I will usually shift the white balance slightly to the warmer side of the spectrum as this is more likely to be “pure black”. I don’t worry about small areas of blue at the tip of the snout and between the ears. This is totally normal.

1. SOOC. 2. Saturation turned up to 100. 3. White balance adjusted. 4. White balance turned all the way up. (And I would say, he’s probably still slightly too cool!)

You can also add a hue/saturation layer in PS and turn the saturation all the way up. This is a MUCH stronger effect than in Lightroom so be careful what you do with it (eg., don’t try and remove ALL the blue/yellow/colour. Remember, our black coats are not pure black!)

So, how can you get to a more “pure black” colour in editing? (Because it’s totally normal and natural and just the way light and colour works that they will end up blue when taking photos of them. Don’t try and fight it, just take the photos in RAW so you have complete control over adjusting the WB later)

- Correct the white balance (this should solve the majority of problems).

- (Possibly) lower the blue saturation somewhat in the HSL panel in LR. Notice how tentative I am about this point? Because I do NOT want you to completely strip the colour from their coat!

- Use a radial filter to lower saturation from specific points, OR (maybe even better) add yellow to those areas.

- In Photoshop: Use a hue/saturation layer to lower saturation (be careful)

- Or, use a colour balance layer to add yellow (and maybe magenta) particularly to “shadows”

- Or, use a solid colour adjustment layer in yellow (the opposite of blue). Set the blend mode to “colour” or “hue”, and paint it over the blue areas. Lower the opacity, like a lot.

- If you are STILL having a lot of issues with blue, I would suggest your white balance is way too cool.

Snoot School: Training Fundamentals

In this Snoot School, we cover some training fundamentals, especially rewarding, how to shape things in small steps, etc.

I recorded it horribly with a tiny window in zoom, sorry! Might be time for a redo!

A Note on Adding Darkness, a Dark Mood, and the Image’s Exposure

As a teacher, one of my jobs was to observe the work my students were creating – not through formal tests or assignments necessarily – but to see their work throughout the week as we were teaching them things. And then, we would use these observations to guide our lesson – either immediately (omg absolutely nobody has understood the task I set them and they’re all doing it wrong!) or for the next lesson.

So, as I see many of my students creating and experimenting with styles and moods and editing technique, I’m starting to notice a couple of things that I wanted to address. This isn’t meant to make anyone feel bad, or like they’ve been “editing wrong” but more to clarify some things, and to give you some things to think about while you’re editing and working with curves layers, creating dark and moody or deep dark forest images and so on.

1. Be Careful Where You Try and Create Darkness/Manipulated Light

There is a bit more on this in the 3rd course where we look at locations. But as with many of our snow photos, if you have a scene which is quite “open” eg a wide grassy area, trying to shape light there (especially into a spotlight effect) doesn’t really make sense.

We have to assume that the light is coming from one or two sources: the sun, or the sky. In the case of backlight, there are two light-sources. In most other cases, we have only one.

In (most) cases, light comes from above, and fans out. In some cases (backlight) the sun can be fanning out from directly behind the dog, or it can be out of camera, and therefore we can give the impression of it fanning out from one side.

However. If we are taking photos in an open area, with nothing to break up the light (eg., no branches that it’s coming through) and/or nothing that would stop/disrupt the light on its way to the ground, then it doesn’t make sense for it to be disrupted.

Let’s have a look.

Open Location, Even Light

Here we have a “What not to do” situation which I whipped up quickly for this lesson. In these two images, the dog is in a wide open space. The light is even – though slightly more to one side than the other. The budding student, seeing this, creates a spotlight effect hitting brighter side of the dog, shadowing and darkening the other side of the image and background.

But this does not make sense. Why? Because, in this location, with this lighting, the light falls evenly across the entire ground and probably across the background (but not always). There can’t be a spotlight effect! Particularly in the cast of the 2nd image, half the sky is dark. And yes, I’ve overdone it a bit for this purpose, but sometimes it’s hard to see these effects if they’re more subtle and you’re not used to looking for them.

I have included some examples below of times where I have done a pretty “even” fall of lighting (eg., the whole ground is evenly lit, evenly shadowed, or slightly shadowed in the foreground). I suspect I have a preference for dogs looking forward when I’m unable to spotlight them due to the surroundings (and I will usually then shape light from above instead). In the snow images, I WAS able to darken the edges of the background, because they were closed in with forest/trees! However on the 3 landscape images, I would NOT have done that, as the sky does not get darker at the edges.

Open Location, Sun Spotlight?

Ok Em, fine, what about when the sun is out? Surely THEN there’s a spotlight effect.

Well…

Not necessarily.

If your dog is out in an open space, a spotlight effect with darkening gets pretty obvious, pretty fast. The example above you can see some very slightly shadowing at the corners of the pier, and I would have darkened the trees on the left and right. But if I had tried to add more shadowing to the ground in a kind of circular shape, it would have looked really strange. I don’t have many (any?) other examples like this because I hate side lighting and sun.

Spotlight in "Closed" Locations

In this case, I’m talking (mostly) about situations where the light source (sun) isn’t visible, as I have another section for backlight coming up.

The arrows in the diagram show light (not necessarily sunlight) coming from the side, and from straight down, particularly if the dog is looking forward.

Here’s where things start getting interesting. In a more “closed” location (note: this does not mean you need to be in the middle of the woods. A location can look like this on the very edge of the woods), we have things which will disrupt the way the light moves. We can believe that light is filtering through the trees overhead on a slight angle, to hit the dog on the side or from directly above. When we include elements in our scene like tree trunks and bushes, we can edit the photo to show where the light “was hitting” (even if we are just giving this impression) and where it was “not hitting”.

Here’s the important part!!

You need to be thinking about:

- where was the light ACTUALLY coming from in this situation?

- where can I show that it was coming from

- if it was coming from that direction, which parts of this scene would it leave light, and which parts could be more shadowed?

- what natural tones of light are in the scene that can help me emphasise the perception of light (Loki in the autumn scene above, with the naturally bright/orange background, and the darker area of bushes to the left).

- Remember that light fans out. It doesn’t fall in a perfect circle pretty much ever. Blend your edits in, or have a reason for why the ground would suddenly be darker than the other part of ground.

The light in this photo doesn’t really make much sense. How is he being illuminated from the side, but both sides of his face are light, and none of the light is hitting the tree – especially near the top of the frame where it gets super dark, or much of the ground around him?

Think about where the light would naturally be falling – how it would fan out, what would be touched by that light and what wouldn’t, and edit gently, blending your darkness seamlessly in. Below: Examples where I have shaped the light to come from either the side, or directly above.

Backlight & Spotlight Effects

Lastly, we have backlight. And this can be interesting because we HAVE a visible source of light – the sun behind the dog!

But as we have a secondary source of light (the sky) we now use this to help us create light effects.

There are two (main) ways you can manipulate images with visible backlight.

- If the sun is actually visible behind the dog, you have to assume that the (strongest) light is fanning out in all directions from the sun. In this case, I would usually work with a mostly light-falling-straight-down kind of edit OR, a spotlight from wherever the sun is in the frame (if it’s top left, I will spotlight from the top left).

- If the sun is NOT visible in the frame because it’s already set, or is off to one side, then I will usually follow the examples from the scenarios in the last section, in terms of thinking where the light actually was, what elements I have in the scene to help me manipulate the perception of light, and so on. Again, I can’t be too heavy-handed because the strongest light source is behind the dog. Subtlety is key.

There is also one of Journey looking up at some hazy light. Again I really emphasised the shape of this light beam because it was like with sunbeams that on the day, and you can see the sun in the image. However, in reality the sun would flare out much more and really evenly light the scene.

I also don’t want to crush your artistic visions and style – so of course it’s up to you to decide how much, where and when you darken things. But I think it’s better to start with thinking about keeping it natural, and gradually experiment with adding drama.

Exposure

The last point I want to make it about exposure.

I’ve noticed a lot of images lately which are embracing the dark and moody mood (yay!) but as a result the whole image is quite underexposed, including the dog.

We do not want our dog to get lost in darkness. With every one of my images, the white part of the dog is as bright as it can go before it becomes blown out, and the blacks are as bright as they can go before they turn a weird grey. Check your histogram in Lightroom though don’t use this as an absolute rule. The “perfect exposure” of a normal everyday image is supposed to be a nice arc – from shadows rising at the midpoint, and down again for highlights. Something like this:

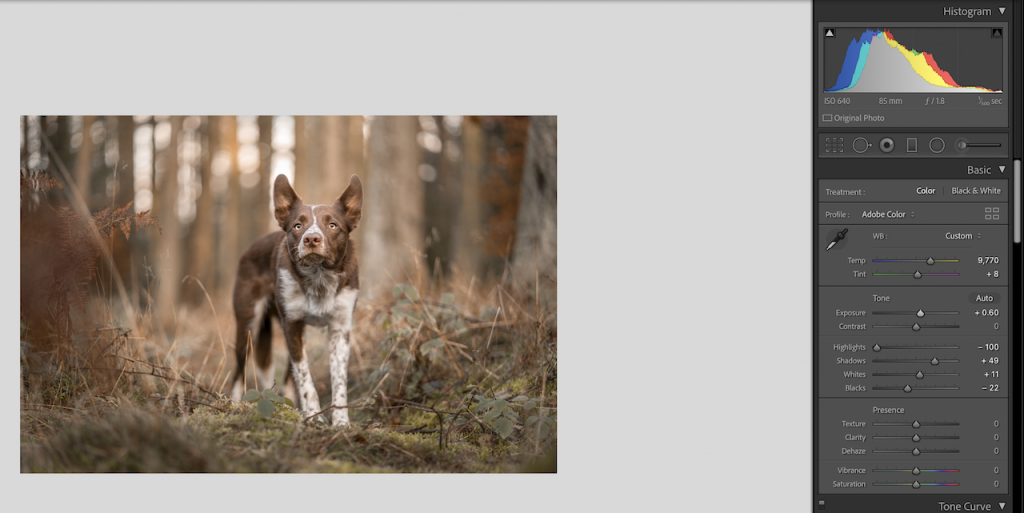

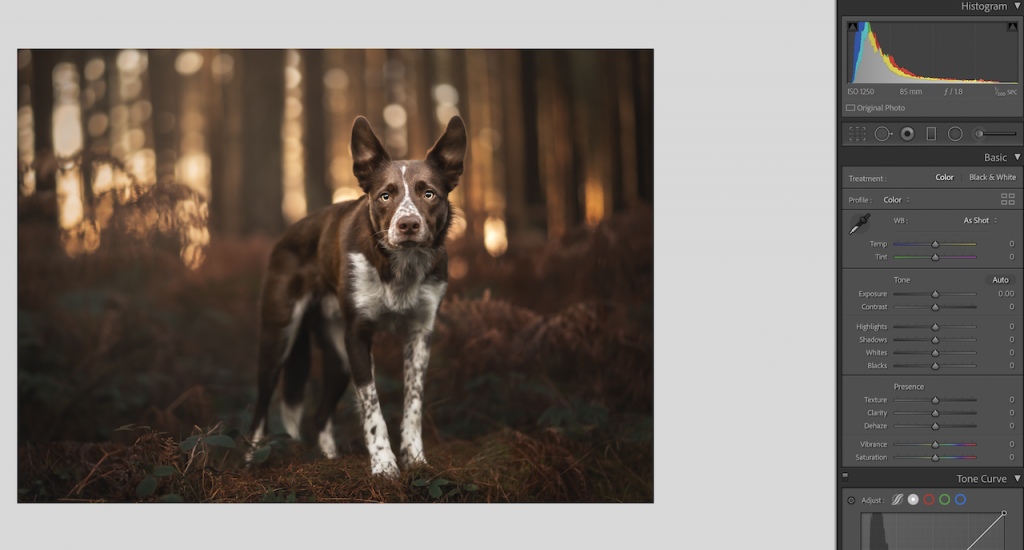

Now this is obviously not my style, and not the look I’m going for! Most of my images end up with the histogram gathered somewhere down the shadows end. Like this:

Note, however, that the histogram isn’t converged right at the left hand side, and there is still a bit of an arc, or an upside-down V-shape to the curve. Let’s compare a couple of images. These are ones that I edited already but I was having trouble finding examples that matched a few that I have seen on Instagram from students (and again, this absolutely isn’t meant to make you feel bad about your editing! This is 100% part of the process, and it’s so normal for us when we learn something new to take it a bit to the extremes. This is more about me seeing something that I need to clarify or explain to help you guys out).

Have a look at the histogram on the darker image, vs. the lighter one. It’s a subtle difference but I hope it just starts to tune you in to checking it.

These images I’ve been seeing are a mix of either deep dark forest ones, or backlight ones. Sometimes the face has been brightened a bit, but in most of them, the dog is getting quite lost in the scene because of how dark everything is. This MAY be a location problem – remember that we need plenty of light on the dog’s face in order to keep them nice and well lit. I know when I first started I was taking photos in the middle of the woods with backlight and just could not physically get enough light on the dog’s face. It was a hard lesson to learn, but I got there eventually.

It may be a too-bright monitor, or editing in the dark. Or it may just be exploring creating that dark forest mood. But I encourage you to:

- check the histogram on LR. If everything is bunched up right down the blacks end, add some exposure (maybe +.30 or +.40. I usually do this anyway after saving from PS! One last pop of light since I tend to go too dark!)

- if you think you might be making things too dark, try editing with your monitor a step or two darker. Mine is usually one step darker than “correct” (as I said, I edit dark!)

- right click on the background of both PS and LR and change the colour to light grey or white. This will make the dark areas look extra dark. How does it look now?! If you are always editing on dark grey or black, things will look nice and bright when they aren’t really

- In LR, press “J” on your keyboard to check for highlight clipping (too bright areas) but also blacks clipping (too dark areas!). This may help, or it may not.

- Lastly, ask yourself: can I clearly see my dog? And of course there might be times where you only want to see the outline of the dog with rim-light, or you might WANT the dog to blend in. But if your purpose is to make a portrait of the dog, can you clearly see the dog?

This image is about as close as I come to not being able to clearly see the dog, and this was done with a very clear purpose in mind. Even then, I made sure to employ certain techniques to help him stand out against the dark background so that he didn’t get lost in it.

Lastly, if you’re wondering if maybe your image is too dark, post it either in the FB group or on our new forums (oooo shiny) and I’ll have a look and let you know! It would be really helpful to get a couple of examples of these from you guys, as that’s the only way to learn and improve.

Photo Walk in Our Woods

In this video, join Loki, Journey and I on a wander around our local woods.

I show you some of my favourite photography spots and why I chose them, or why I might avoid them, what I look for in the background and foreground, and show you some example photos taken in those locations.

I discuss quite a lot about what “type” of background might give you better results, or different moods and effects. We cover this a lot more in the “locations” lesson of the Next Level course.

Gap Between Trees

In the video, I discuss quite a lot the difference between wide, narrow, and no gaps between the trees, and areas of open sky. Below, you can see some comparison images – one where the dog is in focus, and one where the background is in focus. I don’t have an “open sky” example at the moment.

These were all taken with my 135mm lens so there is a lot of compression (super blurry background on the in-focus shots), and they aren’t exactly lined up 100% correctly but it’s in the same location so hopefully you get the idea.

The “wide gaps” example isn’t as “bad” as it often is, due to the very fine branches creating a kind of texture between the trees. Without those, they would have been plain white, empty spaces, which isn’t so pretty.

You’ll see these examples discussed more in the Next Level Course.

Backgrounds & Backlight

This guide follows the publication of the “Choosing a Location/Photo Walk” resource, after a question about the direction of backlight/the sun in photos.

These diagrams will also be in the Next Level “Backlight” lesson, but they are here if you need them.

Of course, things like blown out highlights, sun haze and so on, are all dependent on your settings, how much light is on the front of the dog, the angle of your camera and lens and so on. I’ve included a few examples (some pretty much unedited) to show you how each scenario can look.