I will preface this lesson by saying that my speciality is not landscapes, nor dogs in landscapes – if you’re here, you are hopefully familiar with my photography style already! But hopefully this lesson will give you some information about getting the most out of epic landscapes, next time you find yourself in one!

About Dogs in Landscapes

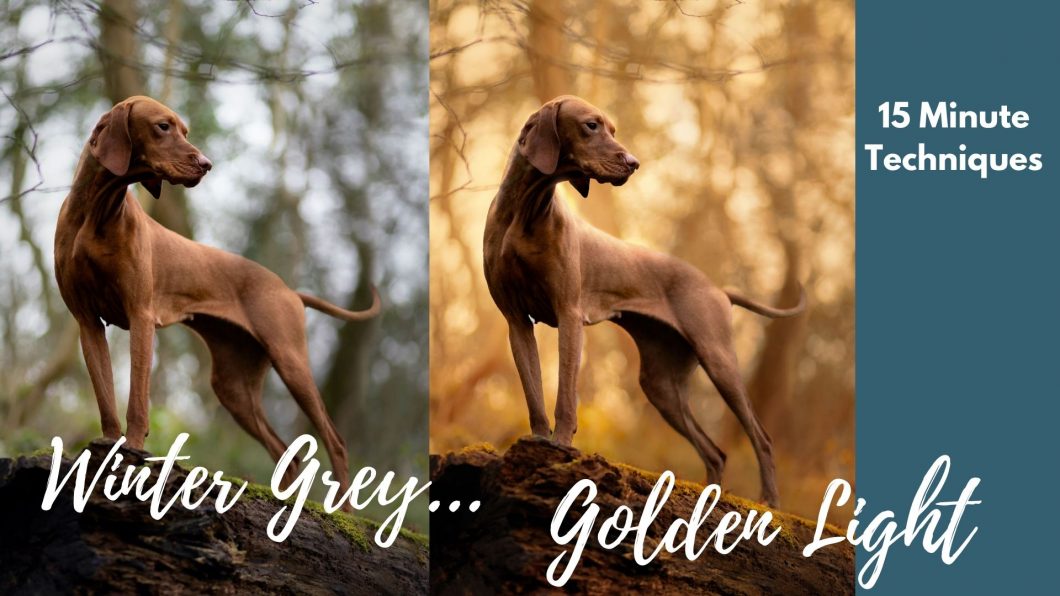

Finding a balance between showing off a landscape scene, and not losing your dog within it can be a challenge. Unlike our normal portrait photography, where all the focus is on the dog, his expression, his pose, with a smaller emphasis placed on the scene around him (usually), dogs in landscapes seek to show us both the place, and the subject within it, often in equal parts.

Some landscapes can be smaller or more intimate: think waterfalls, ferny glades or glens, a foggy mossy forest.

Others are huge, and we want to strive to show the magnitude of the mountains, or the far reaching distance of an endless horizon, or the stretching white sands and blue sea. In this case, playing with the size of our subject within the scene can help to alter our perception of the size of the landscape. Mountains can dwarf our subject and make them feel small beneath them, or our dogs can be conquerors of them. It all depends on how we show the scene.

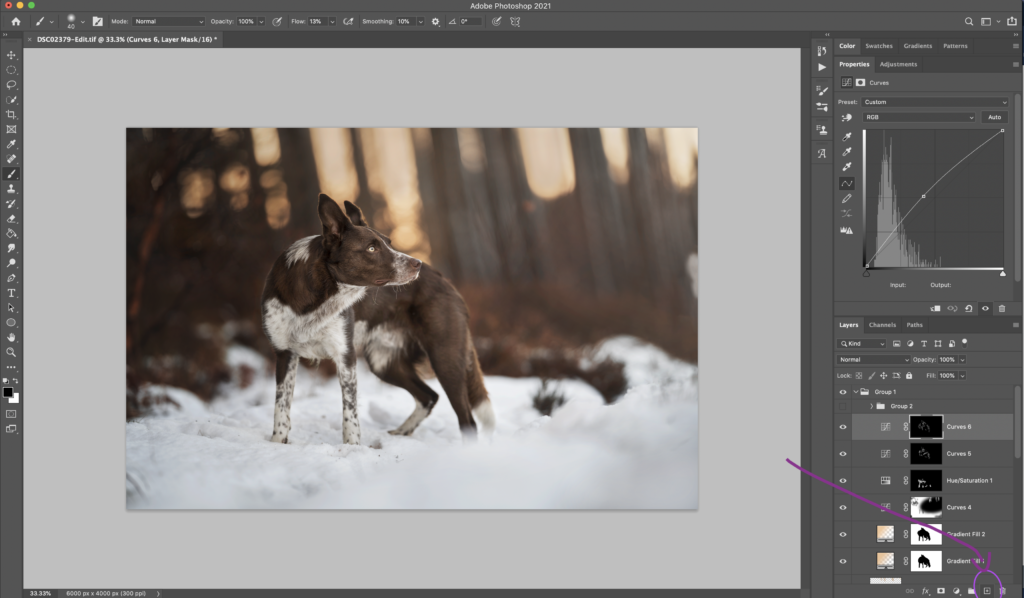

These two photos above were taken at the same place, and are very similar in terms of pose, weather, etc… however in one, we get the feeling of the magnitude of the scene, the grandness of the valley and Journey’s insignificance within it. The photo on the left may have been interesting taken from a lower perspective so he wasn’t getting so lost against the background but he stood himself there and this was a split second candid shot.

The photo on the right still feels large, but the emphasis has shifted (in my opinion) to Journey. Neither of these are right or wrong necessarily, it is just worth considering as you’re setting up your own landscape photos.

Both are only very lightly edited, so it’s possible with working the light a bit, that I could draw more attention to Journey particularly in the photo on the left.

Almost any outdoor space can become a landscape. The difference to our normal portraiture is our focus. As mentioned above, our normal portraiture aims for compressed backgrounds, pretty soft bokeh, and a very narrow depth of field, blurring out most of the scene.

Landscapes will aim to show much more of the space the dog is occupying, probably (though not always) with more detail, a wider depth of field, and a smaller emphasis on the dog alone. That being said, as you can’t make a photo of a dog sitting on an empty field particularly exciting, you probably can’t take a photo of a normal, relatively unexciting landscape and expect to make it epic. There is a reason we have to climb mountains for the best views.

Also, keep in mind that simply using a wider lens, or narrower aperture in order to capture more of the “landscape” when in a heavily wooded forest, probably isn’t going to get you the results you’re after (except in some specific circumstances!) as all that extra detail, all those criss-crossing branches, bushy undergrowth, tangled weeds, and tree trunks will suddenly make your scene much busier, rather than more epic. Dead straight trees with less “busy” undergrowth (I’m thinking redwood forests or pine woods with pretty ferns) will work better…. but will still probably be best when straddling the line between “landscape” and portraiture.

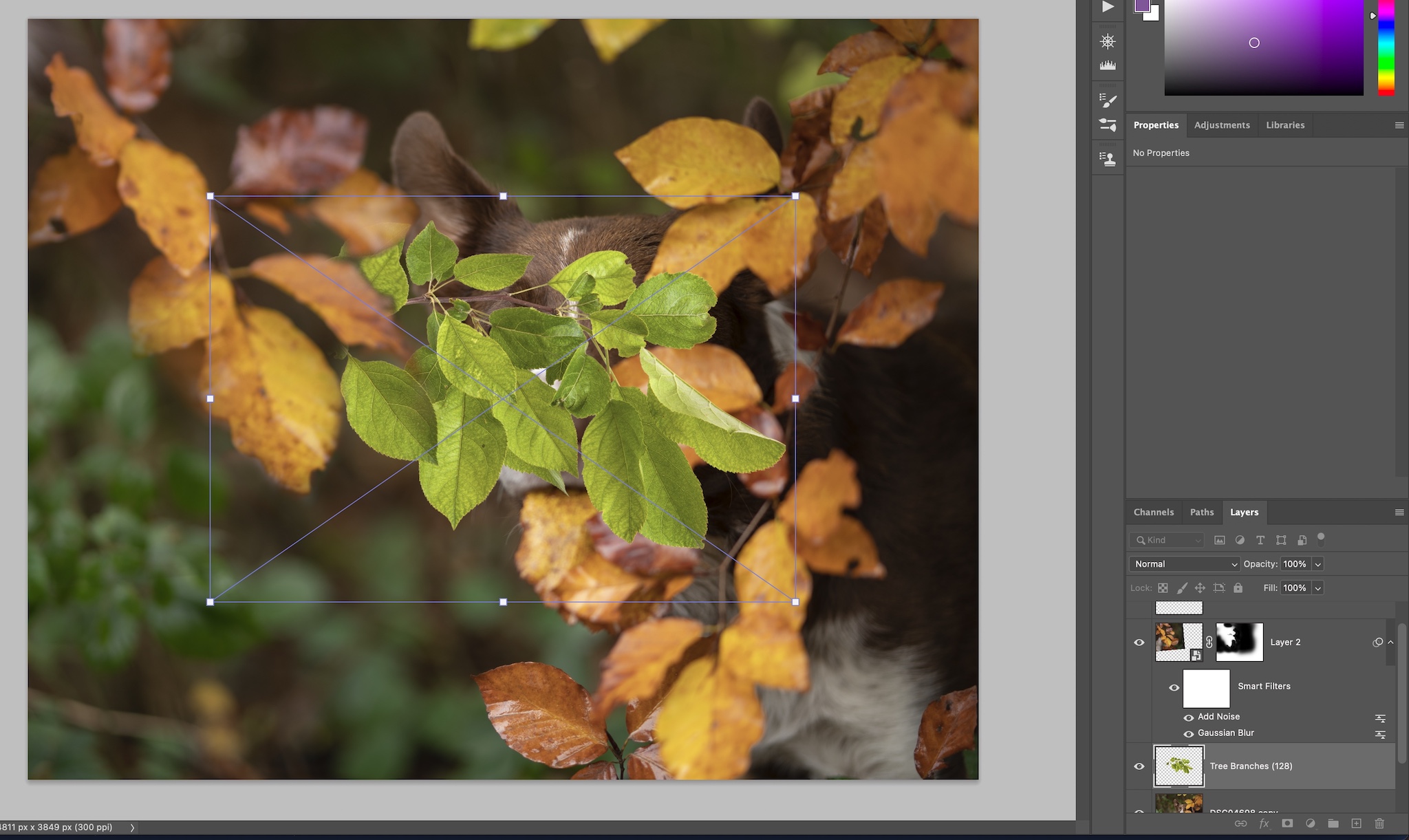

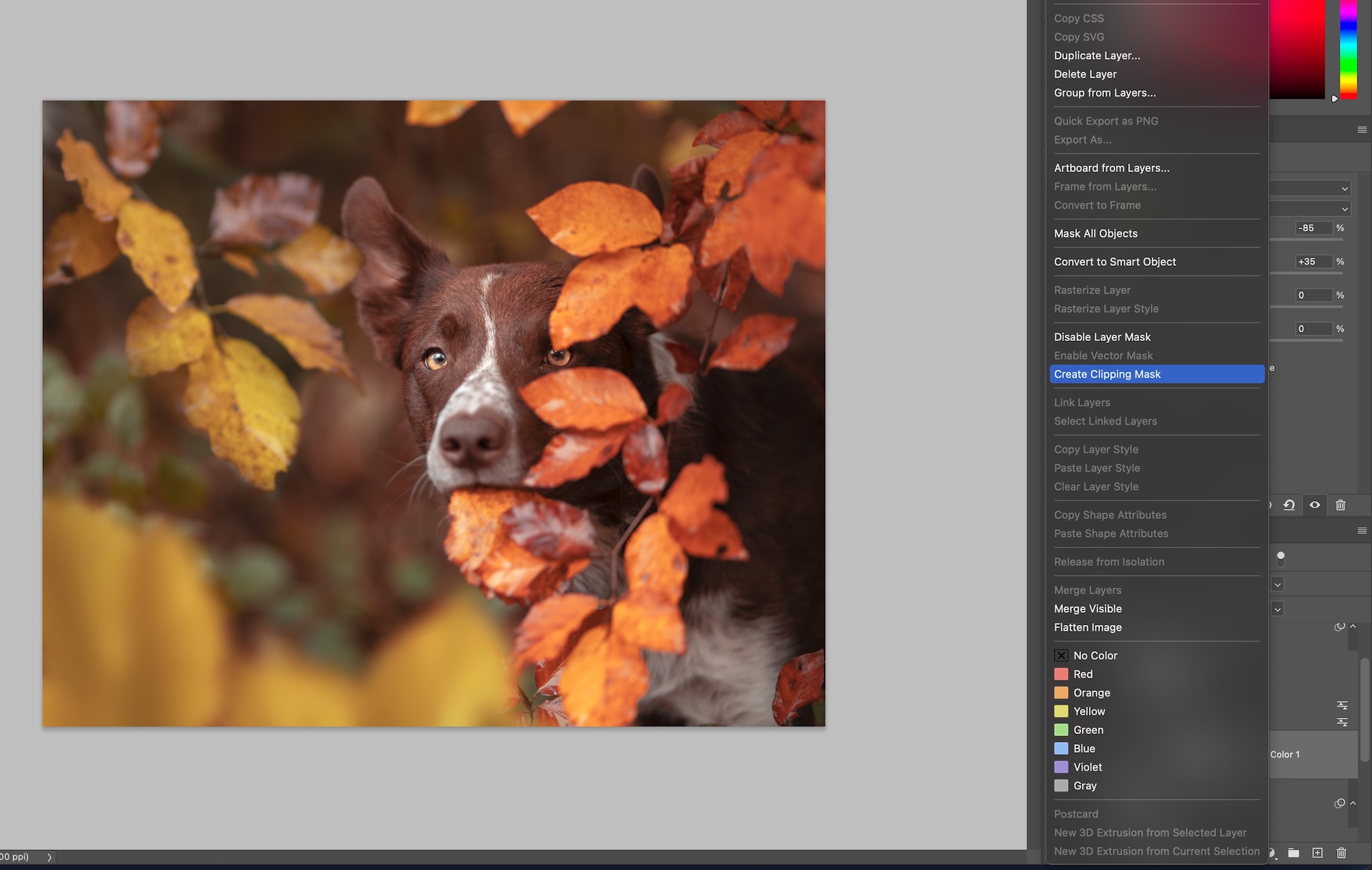

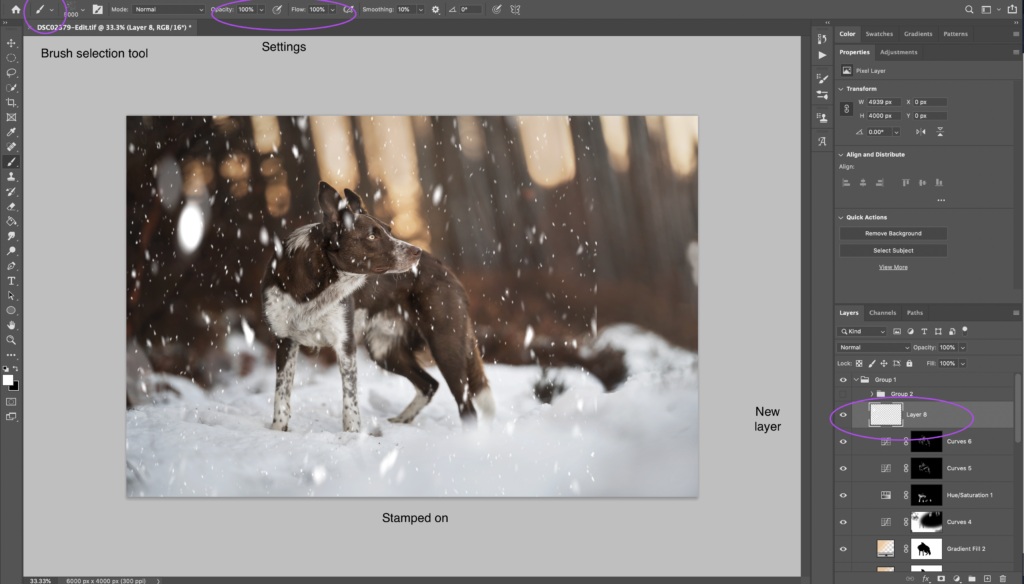

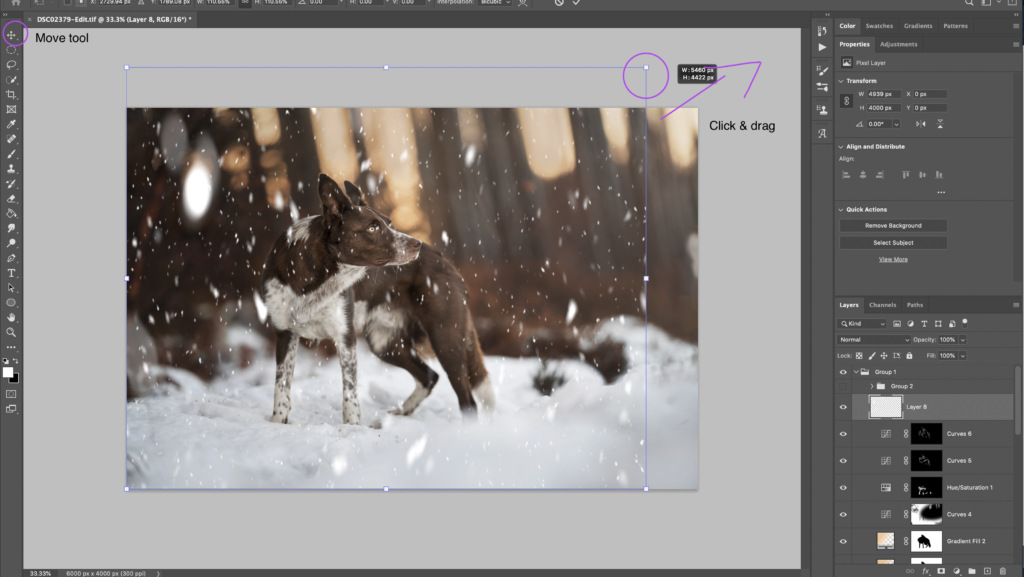

If you’re in the Learning Journey, make sure you check out Exploring > Editing Tutorials, for a full editing tutorial of a landscape photo