Brightness/Contrast

A very simple tool that does what it says on the jar: adjust the brightness, adjust the contrast.

This tool is pure simplicity. You have no control over what part of the histogram or tonal range is being affected by it. It just brightens, and adds or removes contrast.

It could be a good tool to use at the very end of your workflow to add a final “pop” of brightness, and add a little contrast if the image needs it.

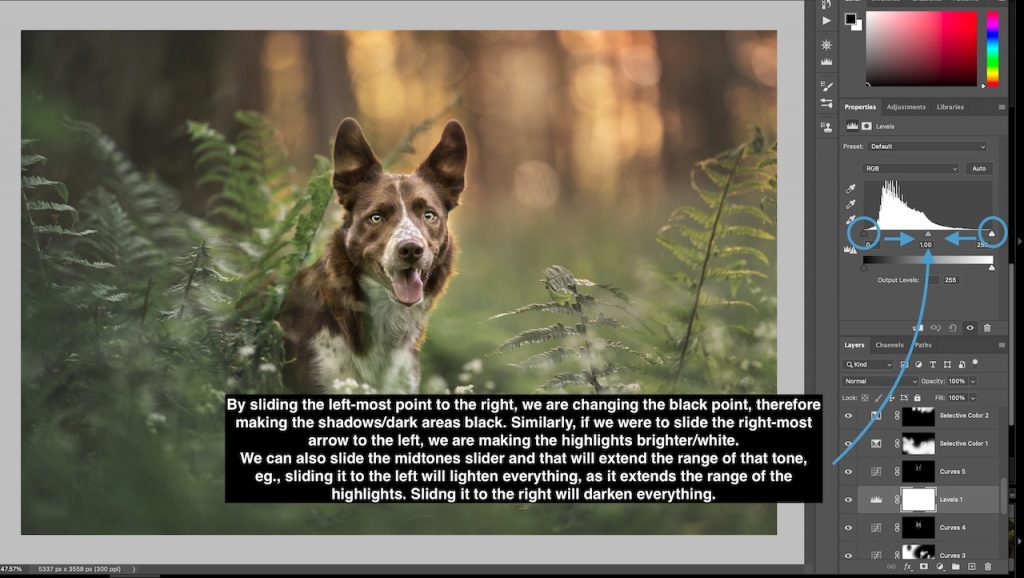

Levels

Allows you to choose from 3 points along the histogram: blacks, midtones, and whites.

Essentially, you are changing where the blackpoint or whitepoint is, or you’re extending the range of highlights or shadows.

So for example if you pull the right-hand side arrow toward the left, you are saying these highlights should be white.

Similarly if you dragged the left-most arrow (blacks) toward the right, you’re saying: “these shadows should be black”.

It is essentially a less flexible version of the curves tool, giving you 3 areas that you can adjust, rather than many (given that you can add as many points along the curve as you want).

Exposure

Another quite simple tool which simply makes a global adjustment to either increase or lower exposure.

There are other options, eg., “offset” and “gamma corrections” but I’ve never had a need to use them for any of my pet photos.

In most of my photos, I tend to add +.20 or +.30 exposure at the end of many of my photos, so you could use this tool for that too.