Table of Contents

A lot of people fear overcast days for photography, when in fact, they are probably one of the easiest, safest, and most flattering weather conditions we could hope for.

Overcast days give us a lot of flexibility not only in the shoot, but in editing too.

Quick Profile

- Soft, even, flattering light

- Neutral or blue tones

- Large catchlights if in an area with view of the sky

- Possibly dull, flat, boring grey skies without texture or interest

- Possibly dramatic clouds, light beams, rainbows and other interesting weather events

- Forests can be too dark

- Shoot any time of the day, but be much more careful of early morning or evening due to lack of light

- Possibility to do sky replacements to swap out boring grey skies

Benefits

- Even, balanced light with no crazy contrasts, giving nice detail to the dog.

- Flattering light.

- More possibilities to “manipulate” light in editing depending on how heavy the cloud-cover is and the location.

- Can get some visual interest from certain cloud types, or really create some drama and epic landscapes

- Nice bright catchlights in the eyes

Challenges

- Blue tones, especially on black dogs, which need to be fixed by adjusting the White Balance in editing

- Sky can look flat and dull.

- Much less light in shaded areas, so photos in the woods will be difficult! Shoot in the middle of the day, at the edge of the shade if you have to.

- Depending on the cloud, if it’s coming and going, you’ll need to continually keep an eye on your camera settings & the direction you’re facing your dog.

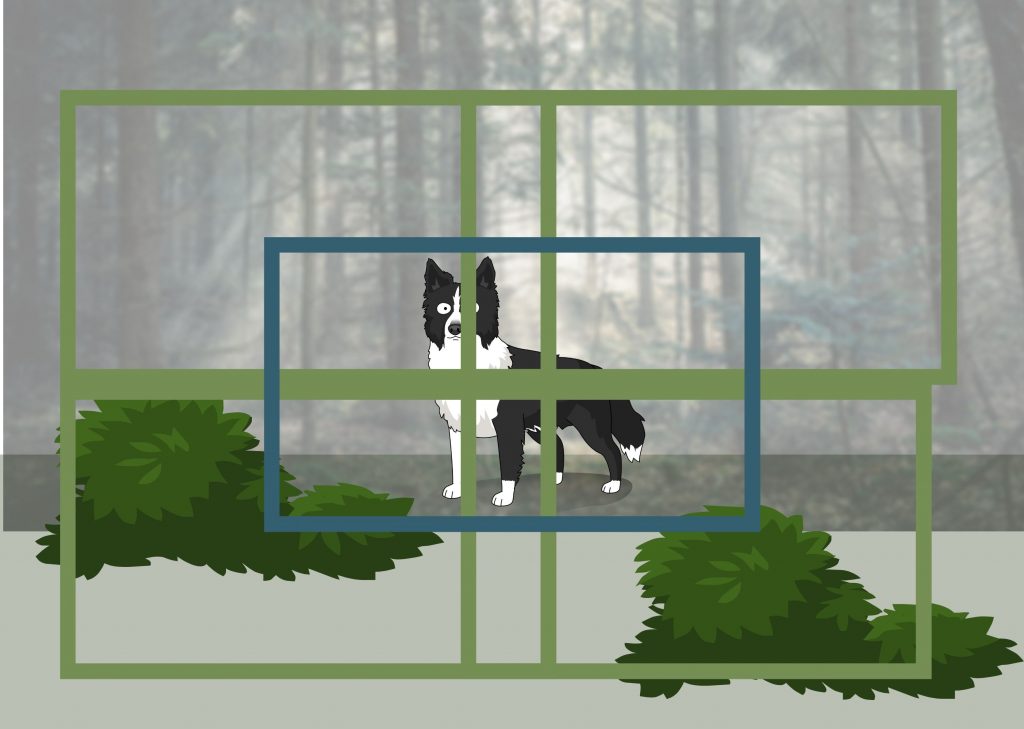

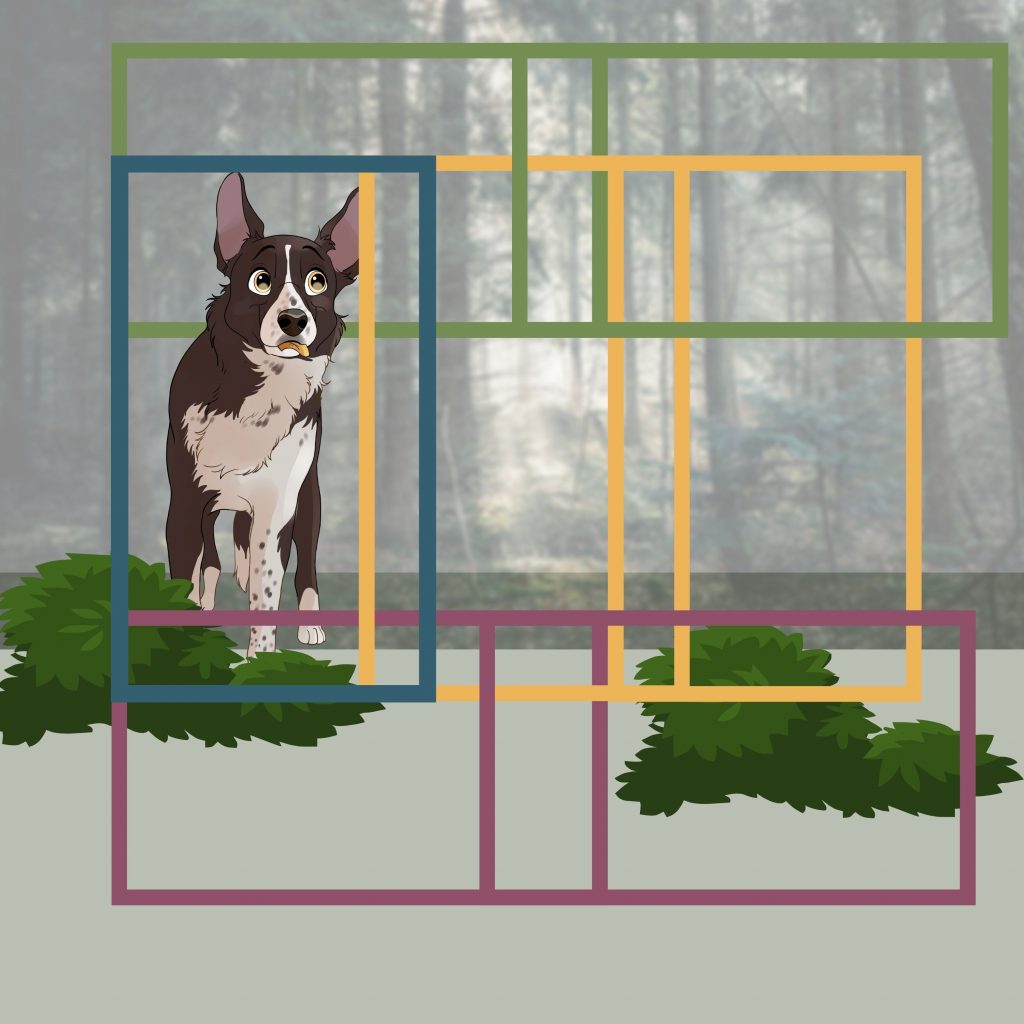

How to Work with Overcast Days

Overcast days can range from very bright, but without the sun really being out, to rather dark, end-of-the-day kind of lighting conditions. You will need to be aware of the conditions and whether they are changing, either becoming brighter and lighter, or darker, and adjust your settings, the direction you’re shooting in and so on, as appropriate.

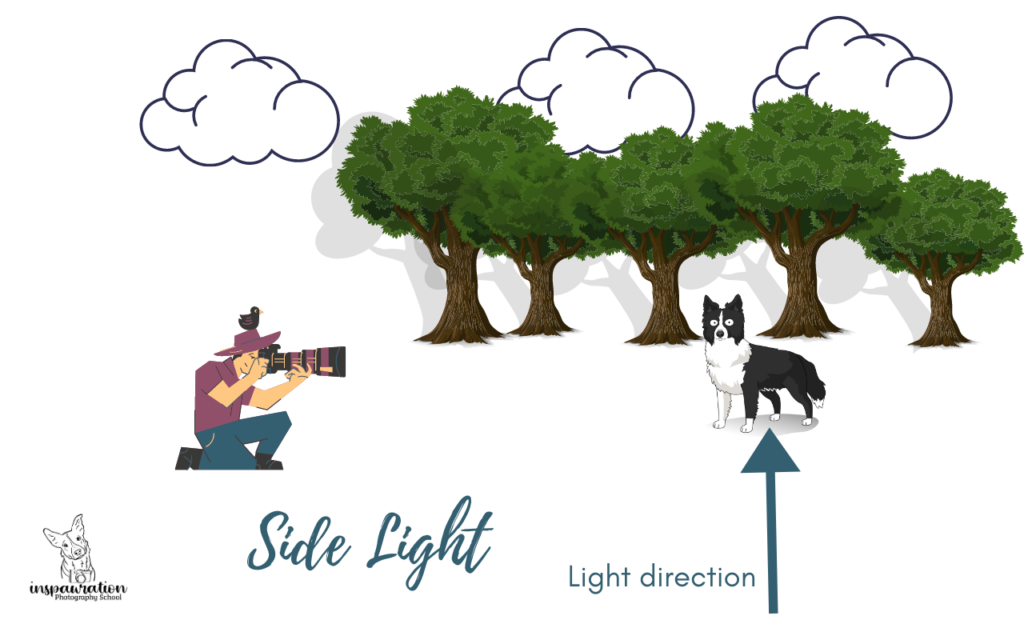

A rule of thumb when considering which direction to shoot in:

Is your subject (or are you) casting a shadow?

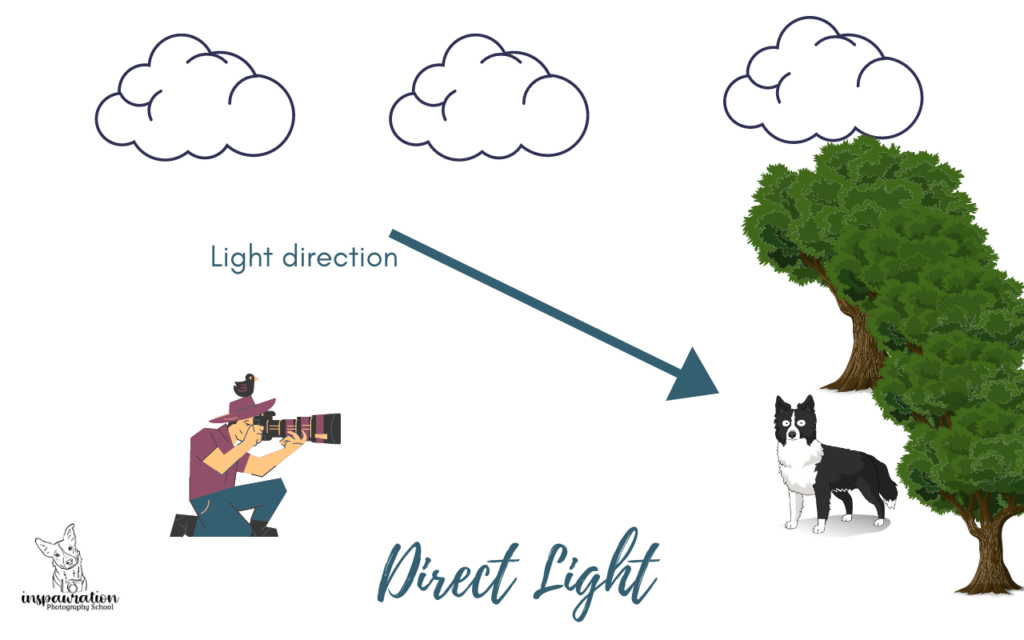

If so, you need to make sure you are using the direction of the light appropriately. Make sure you’re working through the Light Direction lessons as well. This means:

- direct light (having the sun behind the clouds behind you) is probably safest

- side light is difficult but can be dramatic – be especially careful of strong side light when the other side of the subjects is facing an area of deep shadows

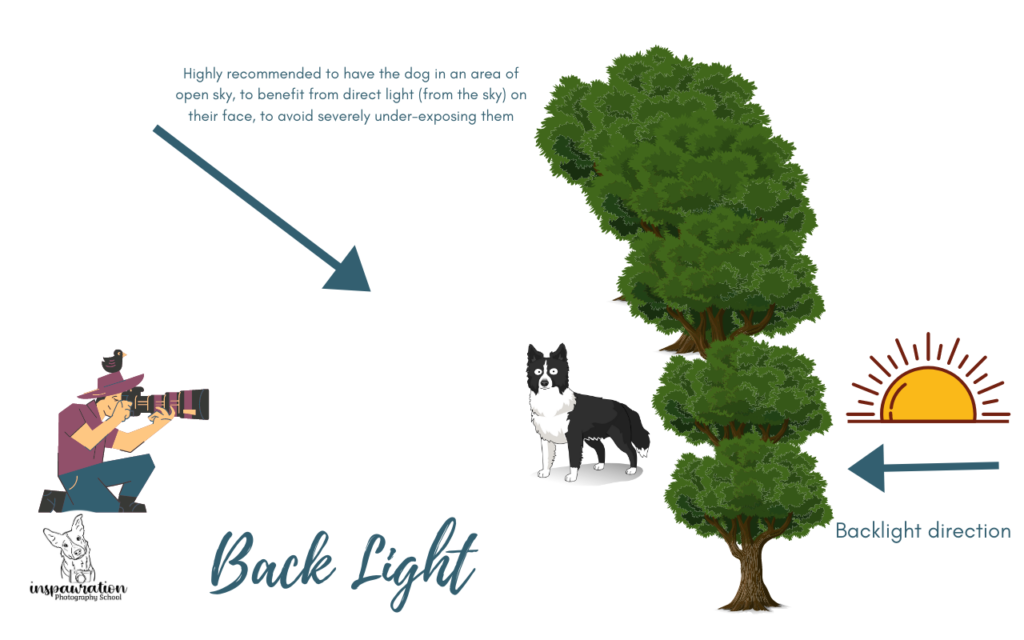

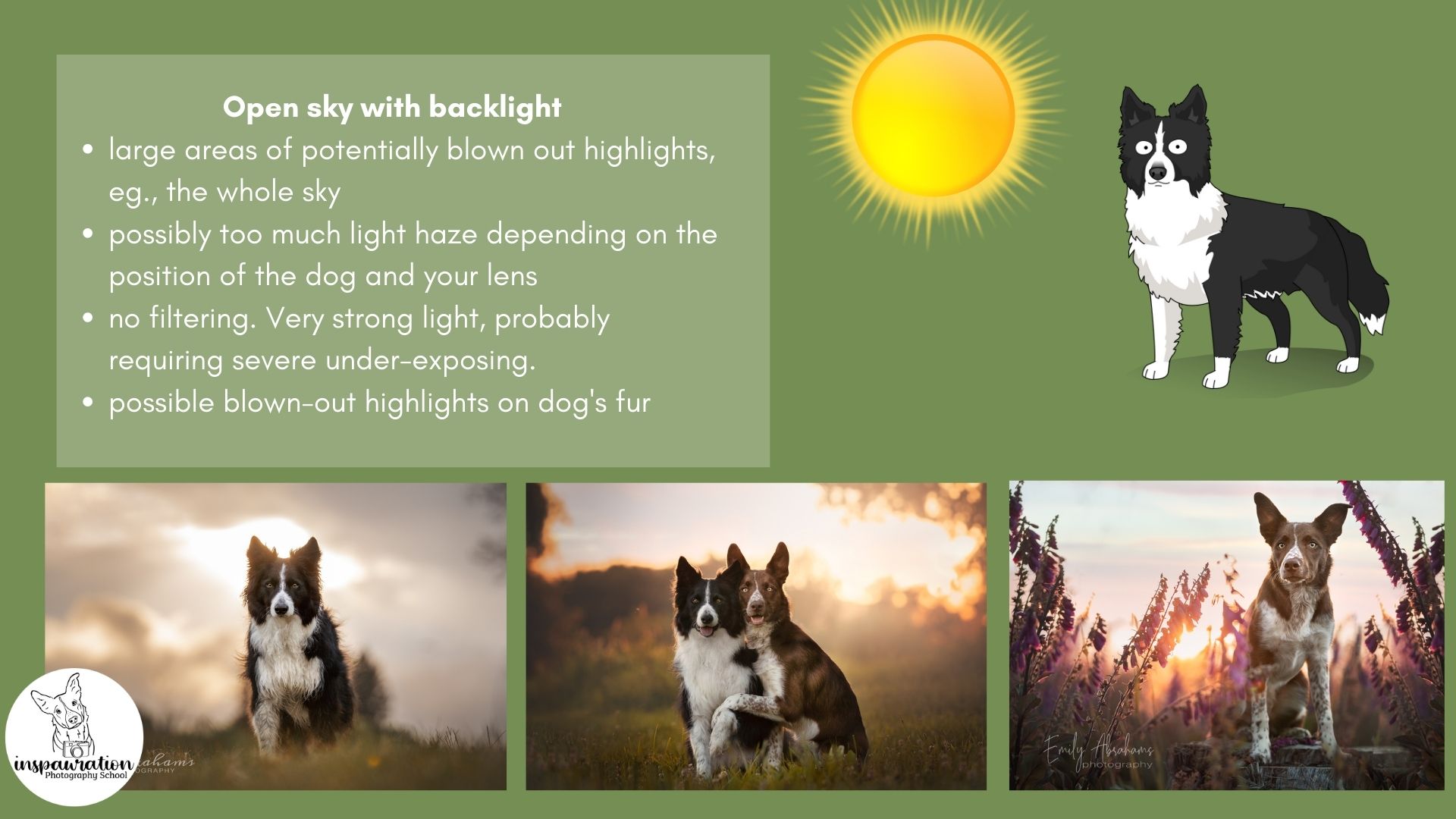

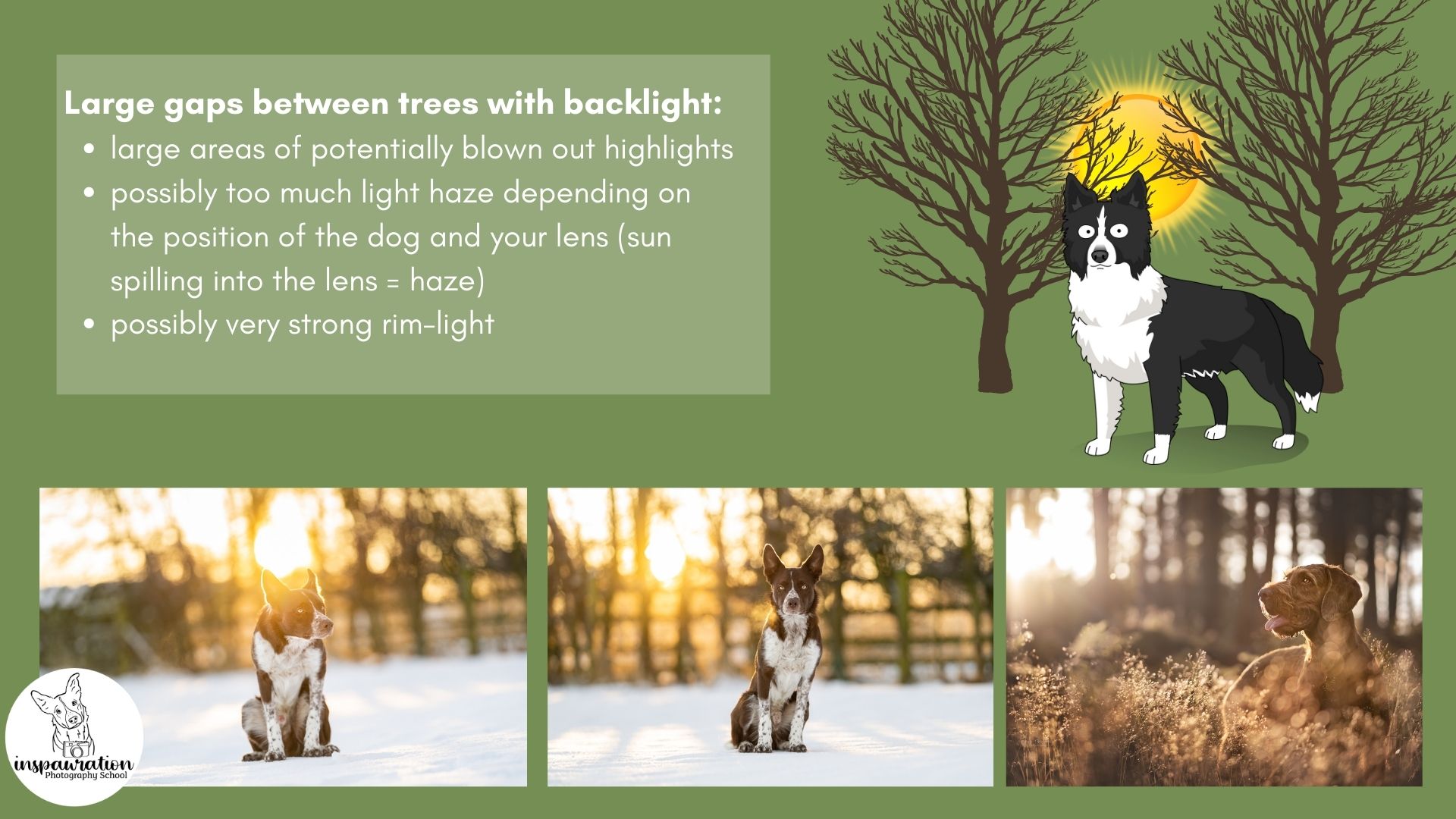

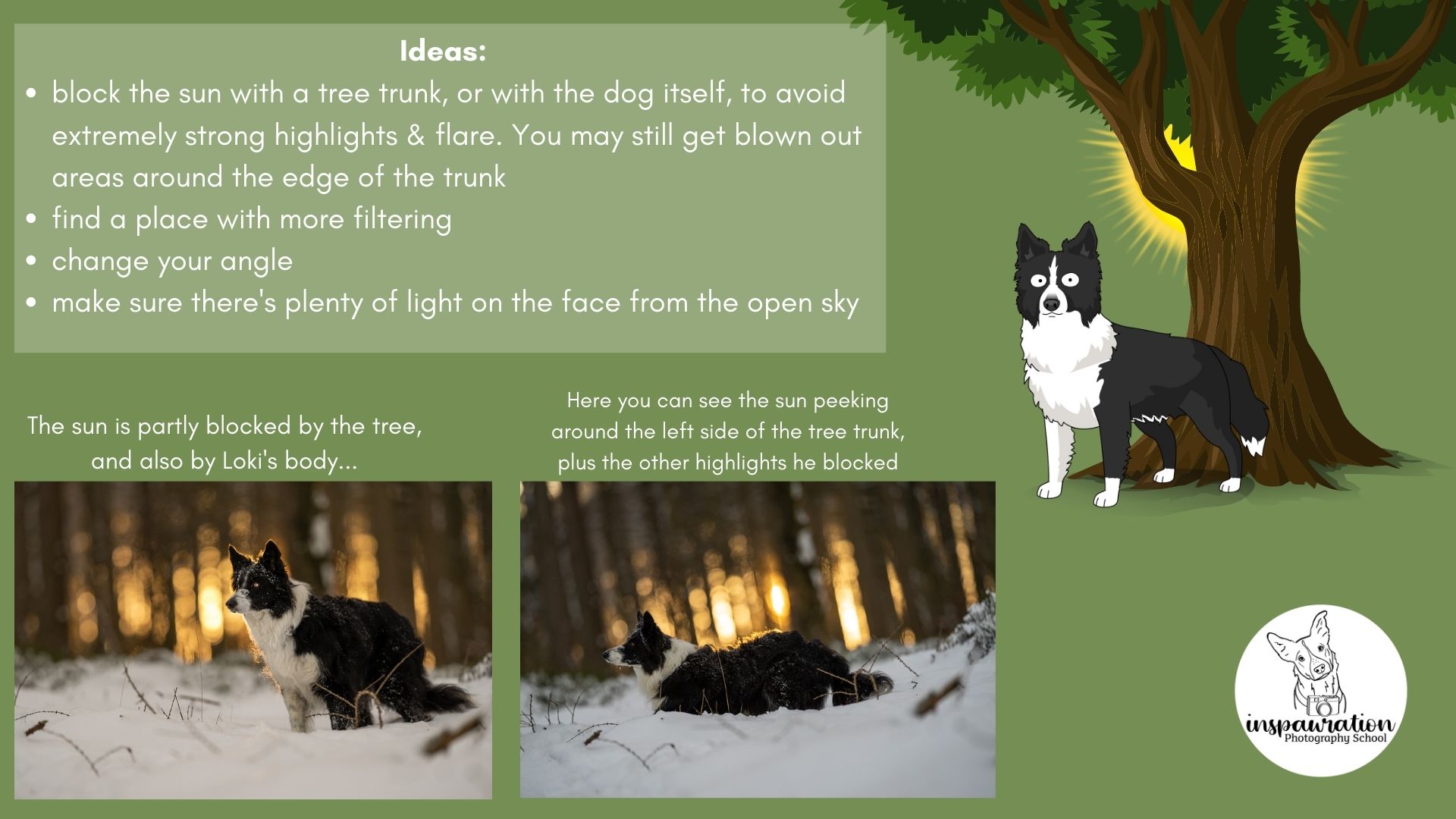

- back-light could be a possibility depending on the height of the sun, whether it’s being filtered, what effect you’re going for, and so on. Just be aware of your highlights, as with all backlight. You may be able to get some interesting white/neutral rim-light depending on where the sun is.

The opposite of course is true on particularly dark cloudy days.

- Watch your ISO, especially if you are in the forest/around the edge of the forest and may be losing too much light. Do not lower your shutter speed to compensate for a high ISO or you will likely end up with blurry images.

- Try using a reflector. You can play with the angles to find one that helps add just a bit more brightness to the face, especially if you have a helper

- You can shoot from any angle around the dog, at least in terms of the sky, as the whole sky is your light source and is omni-directional. Of course if you are at the edge of the forest, having the woods behind you and the open sky behind the dog is not a good idea.

Examples

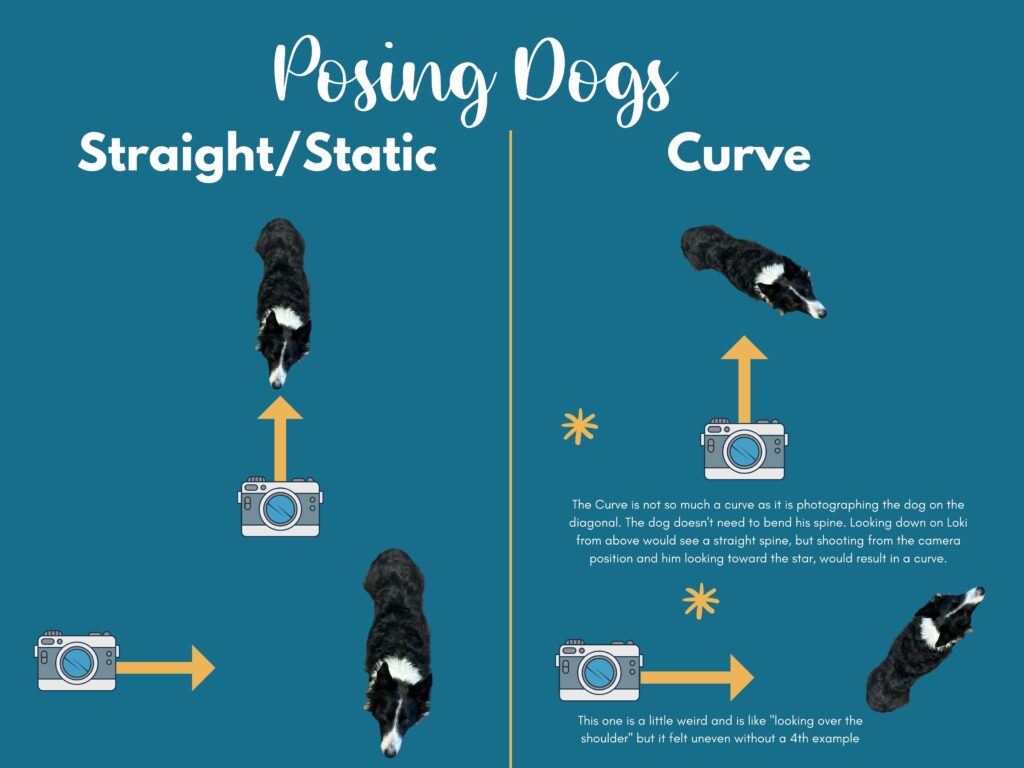

Capturing Dramatic Clouds

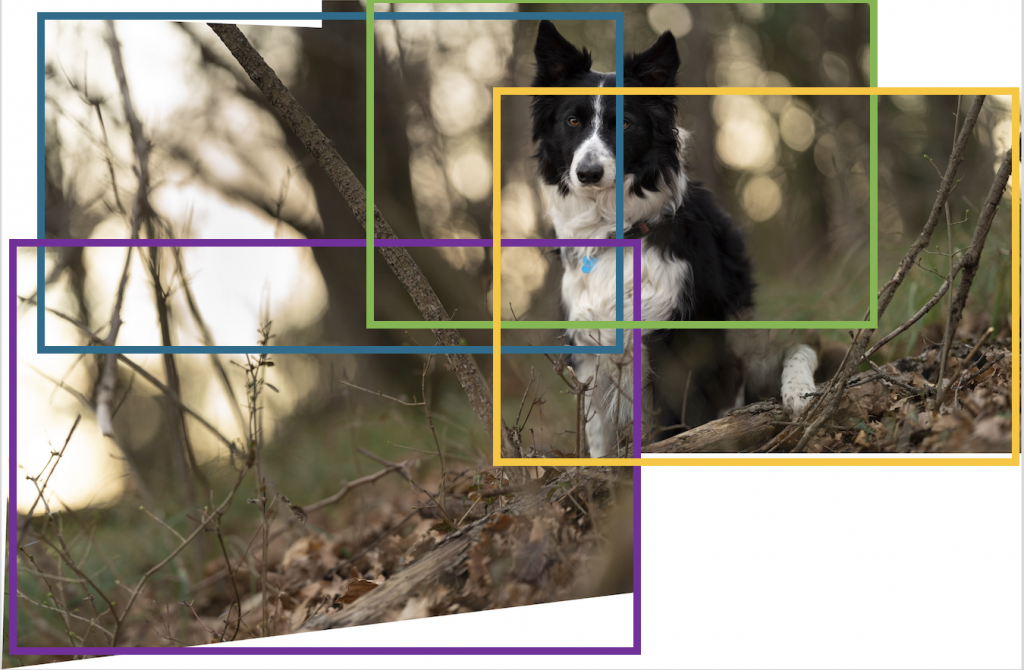

The key to capturing dramatic clouds is thinking about our depth of field. If we think back to the DOF lesson, we want to consider the effect that a longer lens length might have (more compression) as well as:

- Needing to expose for the sky

- Using a slightly wider depth of field for more detail

Two examples here. These are totally natural clouds, enhanced a bit through editing (of course) but the light rays were real. The one on the left was taken with my 85mm at f/5.6. The one on the right was at 44mm, f/4.5

Here is an example of needing to expose for highlights. I was originally going to do this image as a silhouette, hence the ridiculous under-exposing of Diliys. But you can see in the before image that I was pretty close to blowing out the sky where the sun was shining through. Whether your camera can handle this is another matter. Having someone hold a reflector to bounce some of the sky’s light onto the dog’s faces here would be a very good idea.

Also, note how soft and blurry and undefined these clouds are. These were taken with my 135mm at f/3.2.

Below are a couple more examples of bringing back details in the clouds (when there were details in the first place!)

Sky Replacements

When the sky is a flat, dull grey-white, it does make it pretty easy for any editing software to figure out what’s sky and what isn’t, allowing us to replace the sky with something more exciting.

A word of warning, however. If you decide to replace the sky of an overcast day, I strongly advise replacing it with a slightly more dramatic overcast/cloudy day.

Don’t do this:

Unless you are pretty confident you can fake ALL the ambient lighting conditions that would go along with such a scenario, eg., what temperature would the grass/dog be? How underexposed should the dog have been to get such a sky and therefore how should he look now that he’s brightened? What temperature should he be? Should there be rimlight? The hill in the background should be in shadow, since the sun is behind it, but how much? And so on.

Also, blur your sky to the same degree as the horizon. This background is much too in-focus to be believable.

This:

Is reasonably better, considering it was a 5 second job on an unedited image. Here is the original:

I don’t always recommend sky replacements, and maybe that’s because most of my photography isn’t done with areas of open sky (unless it’s twilight or dawn), so I really don’t have a need to replace them. If you live in an area where you are often shooting with wide open grey skies (or even empty blue skies – then you could replace it with a blue sky that at least has a few clouds in it) then this could be something for you to consider.

Just please keep it natural, unless you’re pretty confident that the sky matches the ambient lighting and so on.

Some images with replaced skies. And actually I’m not sure I’ve ever shared these anywhere (the beach ones anyway) because I’m too self-conscious about being called out for replacing the sky!

In the Loki image, the replacement is quite dramatic, as I’ve completely changed the lighting and temperature. For the image of Journey running, I’ve replaced a flat, empty sky, with another overcast sky, but one where the clouds have substance. And for the last image, it was actually twilight. The sun had just set. The replacement I chose was not that dissimilar to the actual sky at the time.

Old Video

This video is a bit old now buy may contain some interesting or useful information, so watch it if you’d like, but it’s mostly here as a bonus!