We’ve talked briefly about looking at the histogram in the lesson on underexposing, but let’s dive into it a bit more in detail.

If it looks like math and you’re not good with math (like me), don’t panic! It’s not as complicated as it looks.

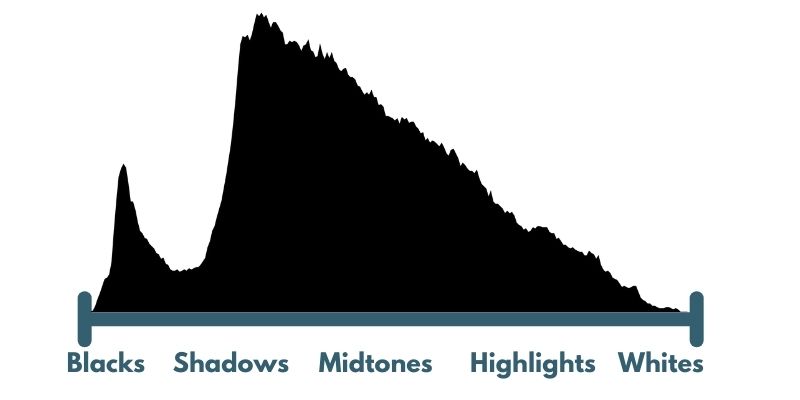

The histogram is a graph that visually shows the range of light in an image, from blacks on the left, through to shadows, midtones, highlights and whites.

What might this photo look like? We can imagine there’s a dark/black spike: something not too big. A dog? A tree trunk? The rest of the photo is reasonably well exposed with a lot of midtones and some highlights. No crazy bright areas though and certainly nothing blown out like backlit bokeh in the background. Probably unlikely an open sky either, as this would show up on the highlights/whites side as well. Something in the forest then? But not a deep dark forest, and not underexposed like many of my photos. Just something well lit, with one chunk of black.

Let’s have a look at some more. Have a look at the histograms below, then click the drop-down to see the photo they’re from.

All photos are straight out of camera.

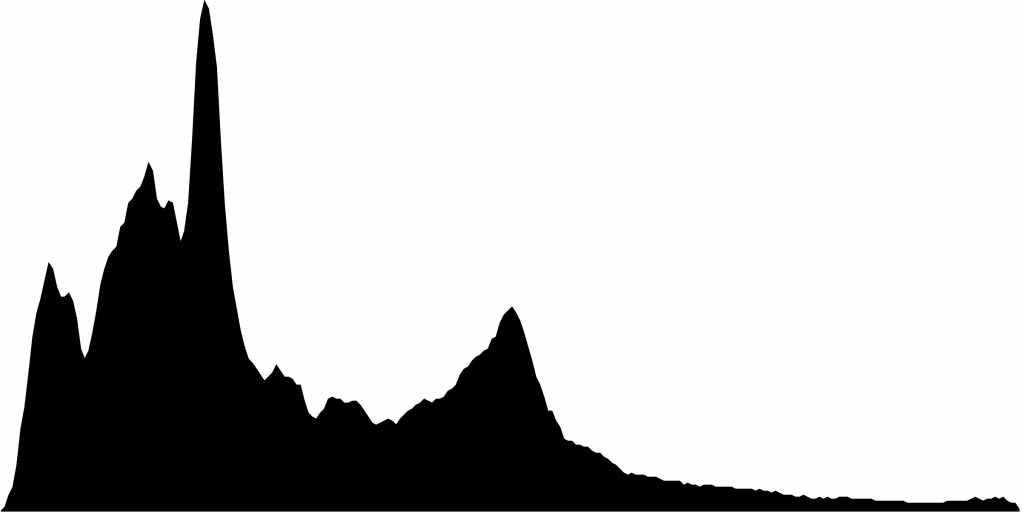

This one has a lot more of the histogram down the blacks and shadows end. This makes sense when looking at the photo, as we have Loki in black and a large shadow area to the left of the photo.

The highlights from the background are quite subtle and not blown out so they aren’t showing up as highlights or whites.

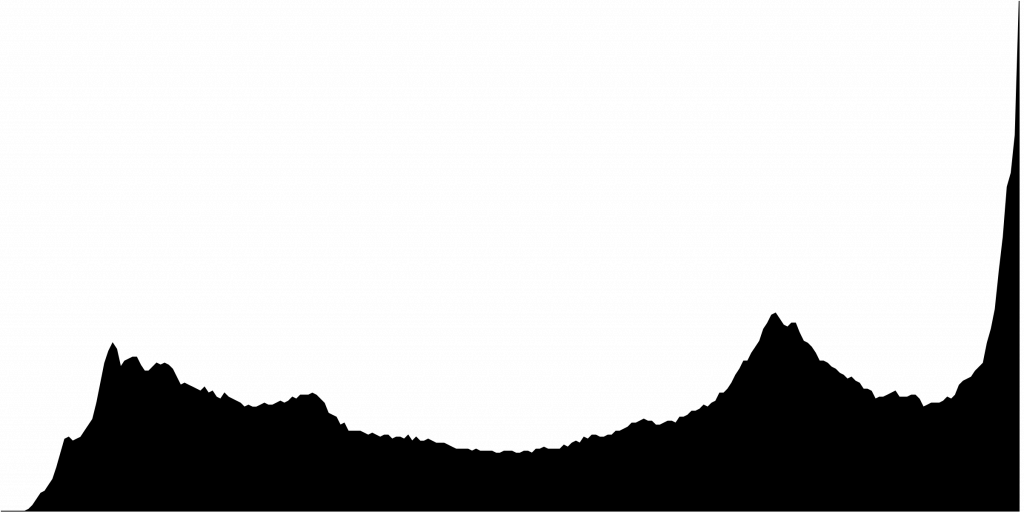

This image is mostly made up of a chunk of shadows (Journey and the plants in the foreground and tree in the background) and a big, problematic spike on the very right hand side, indicating some highlights that have been clipped/blown out and have lost data.

Below you’ll see the image if I lower highlights and/or exposure over those bright areas. See how there’s some parts which are just pure white with sharp edges? These are the blown out parts.

They can be very distracting for your audience as their eye is drawn to the brightest part of the image, and they can be extremely difficult to fix in a way that makes sense and looks nice.

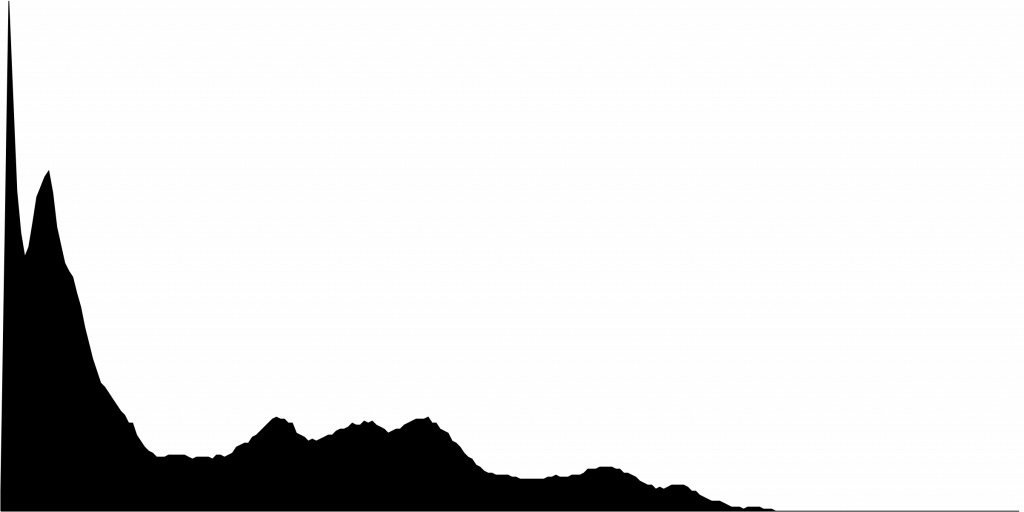

And this is the other end of the spectrum. Here we have a photo with a lot of data bunched up down the blacks and shadows end, with a little bit near the midtones and basically no highlights.

I would be more likely able to fix this photo in editing than the one above, if my camera has decent dynamic range and is able to capture that much data in the dark areas.

Here is the image with the exposure lifted to show you what data has been clipped in the blacks. I have circled this in blue.

Here, we have a photo with a big blown-out highlights problem.

Look at the right hand side of the histogram. See that spike? This is the whites in the background that have been blown out and have no data left.

Editing this photo will be quite difficult, as I will be unable to “fix” these highlight areas easily.

The shadow to the left is likely representing Journey.

At first glance, the histogram of this one looks like a bit of a disaster!

At first glance, the histogram of this one looks like a bit of a disaster!

But look closely! You’ll see I’ve very carefully left a gap between the edge of the graph on the right hand side. So while the highlights are VERY bright, they aren’t blown out.

When I edited this photo I managed to recover a lot of detail from the sky.

Why is this important?

Get into the habit of checking your histogram, either when you’re previewing your photos after taking them but before you leave the location, or better yet, if you can have it up on your display as you’re taking photos.

This will allow you to accurately gauge the exposure of your photos. If you know your camera can’t handle underexposure but everything is bunched up down the left hand side, you may need to fix your exposure.

If you’re taking photos in backlight, and you notice a spike to the right hand side, you need to make a decision about whether to lower your exposure, or deal with the blown highlight.

I can’t make that decision for you: that decision depends on your camera’s capabilities, how the exposure on the subject is already, how your editing skills are and so on.

Note! Your histogram may not show up very small blown out areas, eg., the small part of white on a dog’s snout or a white dog’s back or collar which will be getting a lot more light than the legs or chest. If you know this area is likely to be getting bright due to light shining from behind or directly on the white area, you may want to underexpose just slightly to make sure that those small spots aren’t accidentally getting blown out.